July 18, 2025

7/18/2025 | 55m 35sVideo has Closed Captions

Barry Diller; Tim Weiner; Dr. Jay Bhattacharya

Media mogul and IAC Chairman Barry Diller discusses his new memoir, "Who Knew." Tim Weiner explores the role of the CIA in the last quarter century in his book "The Mission: The CIA in the 21st Century." Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, Director of the National Institutes of Health, discusses current news surrounding the agency and how he plans to lead in a time of division.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

July 18, 2025

7/18/2025 | 55m 35sVideo has Closed Captions

Media mogul and IAC Chairman Barry Diller discusses his new memoir, "Who Knew." Tim Weiner explores the role of the CIA in the last quarter century in his book "The Mission: The CIA in the 21st Century." Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, Director of the National Institutes of Health, discusses current news surrounding the agency and how he plans to lead in a time of division.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Amanpour and Company

Amanpour and Company is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Watch Amanpour and Company on PBS

PBS and WNET, in collaboration with CNN, launched Amanpour and Company in September 2018. The series features wide-ranging, in-depth conversations with global thought leaders and cultural influencers on issues impacting the world each day, from politics, business, technology and arts, to science and sports.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(dramatic music) - Hello everyone and welcome to Amanpour & Company.

Here's what's coming up.

- Because I wanted so much to, I guess, please my mother, it gave me kind of the ability to please older people in the earliest stages of my career in ways that other people weren't prepared to do.

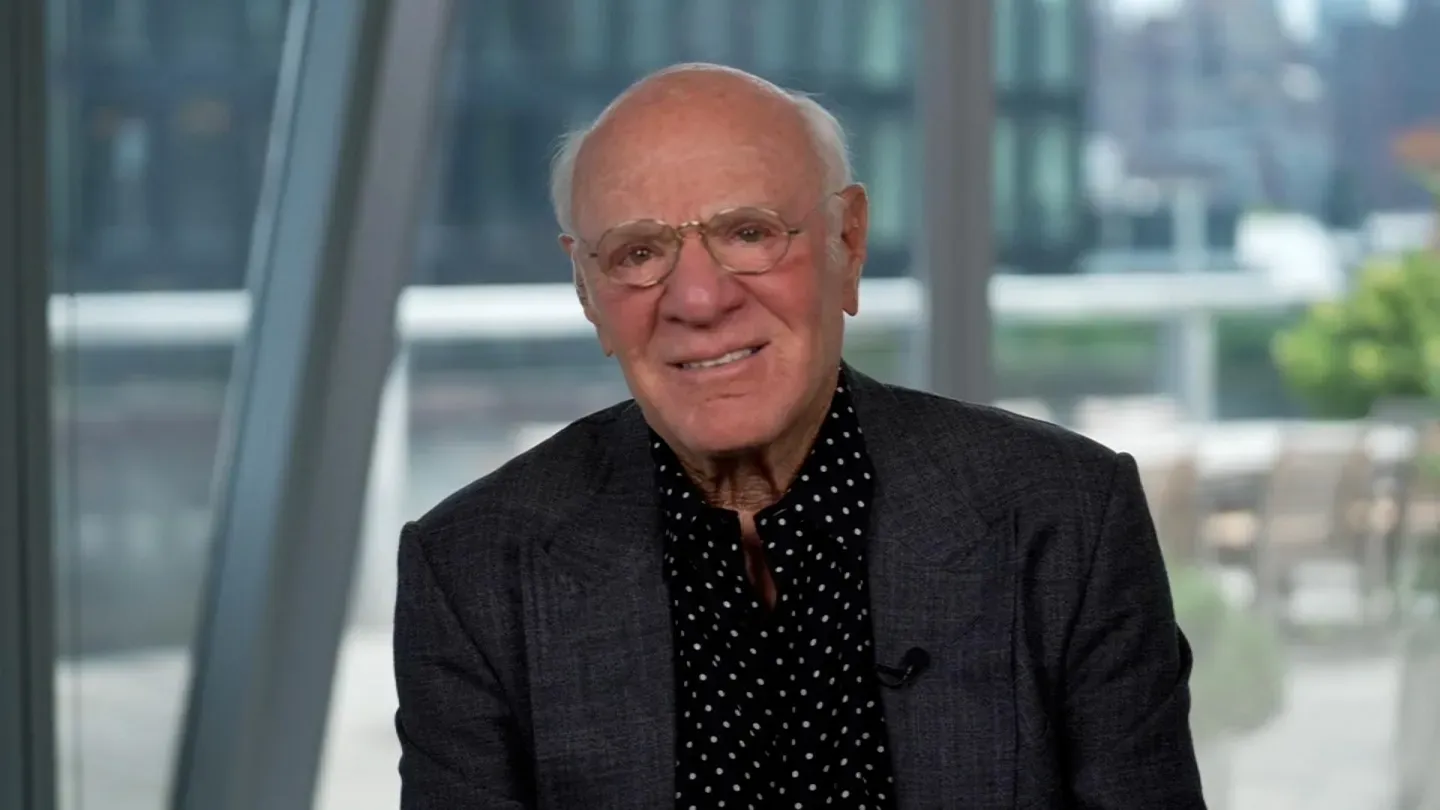

- The man who changed the way we use our screens, media mogul Barry Diller opens up about his dysfunctional childhood and finally becoming the product in his new memoir, "Who Knew?"

Then.

- The CIA was not set up to be a lethal paramilitary force.

It was not set up to erect secret prisons or to inflict torture during interrogations.

It's an espionage service.

It's supposed to spy.

- The Mission.

Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Tim Weiner charts the history of the CIA in the 21st century and warns about the dangers ahead.

Also.

- There's no such thing as democratic science or Republican science.

Science should be something that is for all the people.

And science can't work for the people if basically everyone distrusts it.

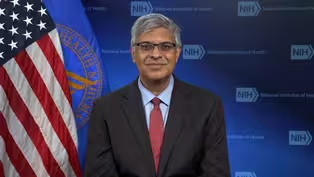

- Walter Isaacson speaks to director of the National Institutes of Health, Dr. J. Bhattacharya about the future of medical research in a world of funding cuts.

(upbeat music) - "Amanpour & Company" is made possible by the Anderson Family Endowment, Jim Atwood and Leslie Williams, Candace King Weir, the Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poita Programming Endowment to fight antisemitism, the Family Foundation of Layla and Mickey Strauss, Mark J. Bleschner, the Philemon M. D'Agostino Foundation, Seton J. Melvin, the Peter G. Peterson and Joan Gantz Cooney Fund, Charles Rosenblum, Ku and Patricia Ewen, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities, Barbara Hope Zuckerberg, Jeffrey Katz and Beth Rogers.

And by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

- Welcome to the program, everyone.

I'm Christiane Amanpour in London.

And we begin tonight with a man who's transformed the way people around the world enjoy entertainment, shopping and even dating.

Just think of some of the biggest titles in film and television, "Grease", "Saturday Night Fever", "Home Alone", "The Simpsons".

Barry Diller helped put them all on our screens.

And it's not just Hollywood he conquered.

As a businessman, he's been ahead of the curve too.

After becoming CEO of Paramount Pictures, aged just 32.

He then went on to launch the Fox TV network.

He made home shopping the habit of millions.

And later, founded the conglomerate IAC, which has owned dozens of brands, including household names like Tinder and Expedia.

Yes, remarkably, in the space of one lifetime, Diller has gone from working with Catherine Hepburn to Sam Altman.

But the story of Barry himself has never really been told until now, in his own memoir, "Who Knew?"

He answers questions that have persisted for decades with candor, even about his personal life.

And I spoke to him about the experience of looking back and opening up, finally.

Barry Diller, welcome back to our programme.

- Nice to be with you.

- So, you know, I've interviewed you about other things before, but I want to start with something you say actually towards the end of your book.

You say, "All my life, I've been engaged "in almost every form of creating product.

"This is the first time I've ever been the product itself."

So, obviously, I want to ask you how does it feel to be the product, but more to the point, because reading it, it's incredibly detailed, it's incredibly candid.

What inspired you to tell this story in this way now, and why now?

Why did it take you so long?

- Oh, I've had a long life, but okay.

So, yeah, being the product, after having taken care of people who are the product for your life, it has taught me a lot of things.

It's very daunting when you are actually the product and exposed.

It's one thing to tell people what to do and how to function, how to direct things, produce things, or create things, but when you are the thing, oof.

Anyway, I've now, it's been out for a couple of weeks, so I'm kind of used to it.

I'm kind of now like just a talking dog, but it took long.

Well, why did I do it?

I did it because I thought it was a good story.

I know story, and I thought, "Hmm, this is a good tale, if I can tell it, "and if I could tell it true," which was the other obstacle.

So I set about to do it, and then I put it away, and I brought it back, and it just took a very long time.

And I didn't think I'd ever publish it, actually, but then about two years ago, I thought, "You know what?

"Actually, the reason is," I was talking to some of my friends, and they said, "Publish it when you're dead."

I said, "No, excuse me.

"When I'm dead, I can't publish it.

"Someone else will.

"I'd rather have agency over it."

And that's the thing that actually committed me to actually go ahead and do it.

- Well, it's a really good read.

It's really engrossing.

It's touching.

It also shows your really sort of hard-ass side when it comes to business, and also your creative side, clearly.

But I want to go, you know, at the beginning, I didn't know, obviously, any of this, even though I kind of know you.

I'm going to declare an interest.

I know you and your wife, Diane von Furstenberg, but the details of your childhood, your upbringing, were really, to me, surprising.

You write, "The household I grew up in "was perfectly dysfunctional."

You talk about your parents who were disengaged, your brother who was a toxic bully, and you never even met one set of grandparents, or most of your relatives, your aunts, uncles, cousins.

Where do you think, or do you think, that led to your drive and your ambition, or not?

- Well, first of all, I think most of it comes from biology.

I mean, I just have this motor ticking around that is almost unstoppable.

But I also think that all the things that happened to me, and all of the circumstances of this dysfunctional family, in odd ways, gave me, maybe I wouldn't, I don't know about saying wanted those weapons, call them weapons, but those abilities, but the fact that I had one big fear, which was sexual confusion, that big fear allowed me, essentially, if you have one big fear, one anvil over your head, then other fears disappear.

So I was able to take all sorts of risks that other people might not take, excuse me, because I had this one big fear.

Now, would I have rather traded and not have that, 'cause it was painful and difficult, and all of those things?

I don't know.

Well, now it's a lot of years later, so I probably would say, you know, who cares?

But I think the things that happened to you, separate and apart from your natural juice, of course, they give you, they both give you limitations, and they give you advantages.

And I, because I wanted so much to, I guess, please my mother, it gave me kind of the ability to please older people in the earliest stages of my career in ways that other people weren't prepared to do.

So that was an advantage.

- Yeah, and I'm going to get to your one big fear in a moment, but about your mother, you tell a story about waiting for her, your mom, to pick you up at summer camp.

You were only seven years old.

What happened that day, and what was your takeaway?

- Well, I got lonely, and I wanted her to come and get me, and she said she would come and get me.

And you know, like those little snapshots that you have in your brain that never go away, you can recall them, they're absolute snapshots, clear as a clear picture.

So I remember I was sitting on basically a tree stump and waiting for her to come hour after hour, and they would say to me, "No, no, come back into the camp."

And I said, "No, no, no, I'm waiting for my mother."

And she never came.

And when I finally realized she wasn't going to come, it was a very cold revelation, absolute, complete revelation that I was not to be protected.

And so it colded me out.

I kind of, I did give up.

I gave up on her, and I gave up on parental protection, 'cause I didn't really have it from anywhere else.

And it kind of, it froze me over.

Luckily, I mean, I think the two things that can come out of this, you either fall apart, or you become very independent.

You also become kind of cold and untrusting that people will help you.

And that, I mean, certainly, I mean, it didn't scare me.

It just resolved in me that I had to be independent.

- Yeah, well, it's a very hard lesson to learn.

And as you say, you're also consumed with this one big fear as an adolescent, and that would have been in the 1950s.

You recognized that your sexuality wasn't of the conventional model back then.

And to understand what you were feeling, I mean, I think this is incredible.

You rode your bike to the Beverly Hills Public Library to find books about homosexuality.

What did you learn in your research about yourself?

- Oh, I mean, again, I do have lots of these snapshots that you can't get rid of them, which is, I remember, first of all, browsing that thing for books on homosexuality, and there were like, I don't know, three, four, five.

And I took each one down and read, like, horrifyingly, that this was just, not just, this was a clear mental disease.

And every book and everything I read in the probable hour I was there was about how this was a sick thing, that there was no mental health hope for someone so afflicted.

And I got back on my bike and I rode back to my house.

And I thought, I really did think, woe is me.

- Well, you wrote, "To my confused adolescent brain, "being exposed as a homosexual "meant the end of life as I knew it."

Well, that's heartbreaking.

But then, I assume you take all of this and you just pour it into being independent, getting ahead.

And of course, one advantage of your growing up in Beverly Hills, you were surrounded by the most famous of the famous, the actors.

You weren't in college at 19, and you had an epiphany that the only career that really inspired you was the entertainment industry.

So what did you do?

You picked up the phone to one of your best friend's fathers.

- Yeah, I was very close to Danny Thomas, who was, at that time, this is the '50s, he had, I think, number one or two comedy series.

I mean, and he was actually William Morris Agency's, theatrical agency's biggest client.

And I knew I wanted, I was drawn always to the entertainment business.

And I'm 19, and I didn't need to get a job.

But I thought, I really wanna learn about this.

And there was this mailroom where they took people in to kind of train them to be agents.

I didn't wanna be an agent.

I knew I could never be an agent 'cause I could never ask anyone to, I didn't have the confidence to say, I'll represent you or whatever.

And I knew I didn't wanna do that.

But what I did want to do was absorb things.

And in those times where before digital, there was this huge file room, and it had, I don't know, 100 big filing cabinets, which literally had the history of the entertainment business going back 70 years.

And so I, essentially, my three years in that mailroom, I didn't do any mail, but I read the file room.

And that gave me this extraordinary kind of, I don't know, foundation for understanding almost every facet of the entertainment business.

I mean, it was just this great good luck, like going to Oxford to read.

- Exactly, and you immediately put it into practice.

You took a job as an assistant at ABC after your mailroom university.

And in really short order, given your youth and inexperience, you launched ABC's famous movies of the week.

It was the first time any network had ever produced its own entertainment.

I mean, you became the head of a department.

You put out dozens of movies a year, and you call it your first startup.

That, I mean, really, in retrospect, can you imagine how that happened?

- Well, I lived through it, so I can tell you.

I mean, it happened, really, because everybody thought it would fail.

No one had ever made original movies for television before.

And so I'm 20, maybe I'm 25 by then.

And I had this idea that we should do this.

And because ABC was the third network, they would try anything.

And also, it was a kind of candy store operation, where if you want a responsibility, you could just take it.

And also, again, they thought it would fail.

So they gave this kid the opportunity, so to speak, or the disastrous potential of making 25 original 90-minute movies.

And so I built this organization, starting with me, and then adding people onto it.

And when you do that, you kind of have to know what they're gonna do.

So I had to learn those tasks, which to me is the best way to learn to become a manager.

And within, actually, after the first year, it was so successful, they ordered a second night.

So we were up to 50 a year.

And then that year, it was so successful, we did a third night.

And so in the third year, we were making 75 movies a year in this operation.

And it started with me, this one person, and had grown to probably a couple of thousand.

- It's incredible, because it really set the stage for many different networks to copy that.

And the whole series and the movies of the week have become sort of what we all now expect, right?

But I want to ask you a fun story, because you populate your book with stories about so many of the amazing who's who of old Hollywood.

Everybody loves Katherine Hepburn.

You have a funny story about her.

You were, I think, in London on a shoot.

You had an issue, and her father was a urologist.

- Oh, oh, oh, wait a minute.

- What's the story?

- Well, her, I'm on a plane to London, and I realize, I feel this enormous pressure to urinate, and I can't.

And I land, and it's got worse and worse.

So I go to the doctor.

He immediately puts me in Guy's Hospital in London, and they, I had a prostate infection, right?

And the next morning, probably, I don't know, five or six in the morning, I was asleep, and at the foot of my bed is Hepburn kind of banging on the metal thing to wake up.

And I say, "Oh, please."

She said, "Look, I came before."

She was shooting a movie at the time in London.

And she said, "I'm on my way, but I had to stop, "and I know exactly what to do.

"My father's a urologist, "and I know what we've got to do to get you to pee."

And I said, "Would you please go away?

"I do not want you to.

"I'm very happy in my bed.

"I don't care if I ever do it again.

"Just leave me alone."

She literally grabs my arm, drags me, she said, "I know what to do," drags me up and down the halls of the hospital.

It's very wide halls.

I know we're going up and down like five times, and I'm like, "When will this end?"

Shoves me in a bathroom, and of course she was right.

(laughing) And then, you know, Hepburn, she didn't say goodbye.

She just left, typical Hepburn.

- And just an amazing woman.

Well, you were saved by nurse or Dr. Hepburn, Dr. Kate.

So listen, so then you went on and on to scale ever higher heights.

You took over Paramount Studios.

But at that time, then you sort of found your family.

You met, as I said, the iconic fashion designer, Dionne von Furstenberg, and you write, "While there have been a good many men in my life "since the age of 16, there's only ever been one woman, "and she didn't come into my life until I was 33 years old."

I think it's sort of love at first sight, but you, you brought it, yeah, tell me about it.

Tell me, tell me, I can see you smiling now.

She gave you something that you hadn't had before.

- It's not, it was, I mean, it was a coup de fo, I mean, she, we, the moment we started talking to each other, somehow, you know, this does happen.

I mean, the moment it was just a complete, it was a rush in ways, different ways, I suppose, for both of us.

But for me, I hadn't certainly expected it, and it was an explosion of passion, and it surprised, certainly it surprised me, but I didn't question it.

I would never question anything like that.

Of course, I mean, how could you question something that was simply powerful on its very own?

And we began our life together, which was in the late '70s, sorry, God, mid '70s.

And then in the late '70s, we broke apart, we were separated for about 10 years.

And then we came back together, and our lives have been, well, there was kind of years of wilderness, but our lives have been intertwined ever since.

- Let me get back to you for the end of your book now.

So you essentially wrote your own epitaph in one sentence, "I've worked hard, helped make some beautiful things, tell some great stories, built companies, and created jobs."

And I don't want to admit that you've been on the cutting edge of just about everything, travel companies, dating sites, online shopping, publishing companies, hotels.

And I just wonder, were you aware, what made you have that courage to just be ahead of the curve on so many of these things that you started and tried and did successfully?

- Well, I had, I mean, I think actually two things, three things.

I had a better sense of better sense.

I had a higher tolerance for risk.

Also, I have innate curiosity.

I didn't, I can't claim it, it's biology, I'm just curious.

And I think the third thing is serendipity.

Things happen to me along the way that are inexplicable.

And that serendipity, yeah, things happen that are, just can't, that they have to be from some celestial, whatever it is.

And it does, of course, depend whether you then have the will, and I have a lot of will, to execute stuff.

But I think it's those things, I guess.

In the end, I think it's actually just biology.

I can't be prideful about it.

- As you write, "Who Knew?"

That's the title of your book.

Barry Diller, thank you so much.

- Pleasure to be with you.

- In a global landscape marred by war, from Ukraine to the Middle East and beyond, intelligence is often critical and course-changing.

There was the massive intelligence failure of 9/11 and false claims of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, which led to the US invasion of 2003.

But fast forward to Ukraine in 2022, and the American intelligence community got it right.

They said Russia would invade Ukraine, and it did.

Now, with President Trump 2.0, there are also concerns over the agency's politicization.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Tim Weiner builds on his history of the CIA with a look now at how it's performed in the 21st century.

That's his new book, "The Mission."

He told me what he sees as the agency's biggest problems and what could lie ahead.

Tim Weiner, welcome back to our program.

- Thank you so much.

- You have continued your amazing saga, really, in history of the CIA.

Let me just ask you first about the Iran situation, which was a whole intelligence and military operation, both by the Israelis and the United States.

So in June, President Trump comes out and says that we've, quote, "obliterated Iran's "key nuclear enrichment sites."

Do you think that was a correct description?

You apparently think it's an example of a problem with the current CIA.

Why so?

- The intelligence, both American intelligence and Israeli intelligence, said that the Iranian nuclear program was set back, but not obliterated.

And when a reporter asked the president about this, he said, "I don't care what the intelligence says."

And this is a big problem.

If you are an ideologue, as our president is, your mind is made up.

You don't want to be confused with facts.

You don't care what the intelligence says.

This can lead to great dangers.

When the CIA tried to convince President George W. Bush that al-Qaeda was about to do something terrible, although they could not tell him the precise hour or place that something terrible was about to happen, he didn't listen.

He did not mobilize the government.

He did not go on a war footing against al-Qaeda, which had declared war against the United States.

There might be something Oedipal about that.

His father had been director of CIA back in the 1970s.

They did not have a comfortable relationship with one another.

Leave that aside.

One Cold War director of the CIA, Richard Helms, once said, "If we are not believed, we have no purpose."

If the president, the president puts intelligence in scare quotes, intelligence.

He doesn't believe it.

He disdains, despises the CIA.

He thinks it is the capital of the deep state.

And this will cause trouble down the road.

Mark my words.

- So, okay, so there's a lot there, and it's really, really fascinating.

And of course, you are taking this episode, if you like, of your CIA history from the beginning of the 21st century, pretty much the 9/11 moment as you've just described and just before it.

Tell me how and what happens, you know, if the president doesn't believe the intelligence.

You said this is a very, very slippery road.

So give us an example.

I mean, we all know, essentially, the George W. Bush Iraq scenario.

There was a huge amount of mixing of ideology, political belief, and mixing up intelligence around that whole 9/11 Iraq war paradigm.

- There were several disasters that followed the 9/11 attacks.

One was that the CIA director, George Tenet, who was a good person, but over his head, said, "Oh, Lord, well, we didn't connect the dots "before 9/11, and now we're going to give the president "all the dots."

Every morning at 8 a.m. for months on end after 9/11, the CIA director would come to the White House with a long list of uncorroborated threats.

He had told every friendly foreign intelligence service in the world, "Give us everything you have, "no matter how far-fetched."

Every morning, 40, 50, 60 threat reports came to the White House.

They're coming for Los Angeles.

They have a second wave of attack.

They've got nuclear weapons, biological weapons, chemical weapons.

They're going to hit the White House.

And the director of CIA, George Tenet, said, "You could drive yourself crazy "believing even half of these threats."

And the trouble was, we didn't know which half to believe.

This drove the White House mad.

It really did.

This is where we lost our perspective.

After 9/11, counterterrorism swamped everything.

The CIA was ordered to be the pointed end of the spear on the war on terror.

The CIA was not set up to be a lethal paramilitary force.

It was not set up to erect secret prisons or to inflict torture during interrogations.

It's an espionage service.

It's supposed to spy.

It's supposed to recruit foreigners to enter into a criminal conspiracy with CIA officers to commit treason against their country and let the CIA know what's really going on behind closed doors in the high councils of the Kremlin, in the Iranian Majlis, in the high councils of enemies.

For 15 years, counterterrorism took over, and that didn't change until the Russians ran one of the most successful covert operations in history, penetrating the American democracy and monkey-wrenching the 2016 election in favor of Donald Trump.

- This is another really interesting inflection point because this goes to the heart of Trump's relationship with the CIA, then and now.

But first, I just want to stay for a minute with Iraq and the famous, infamous false claims, now we know, of WMD.

You quote one former CIA Iraq operative told you, "These guys would have gone to war if Saddam had a rubber band and a paperclip," talking about the Bush administration, Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, all the hardliners.

Again, just there, how did politics become so entwined or corrupt intelligence?

- In the summer of 2002, the Senate Intelligence Committee requested an estimate, a national intelligence estimate.

This is the reporting of all known thought on a controversial or difficult topic.

And they wanted it in three weeks, and they wanted to know what was the status of Saddam's arsenal.

Well, the CIA hadn't had a spy or a covert operations officer in Iraq since 1998.

They didn't have any intelligence.

And what little they had came from dubious sources and one skilled liar, an Iraqi defector, whose code name was Curveball.

The CIA put together this national intelligence estimate with the scantest of intelligence.

And they falsely reported that Saddam had nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons capabilities far beyond what he actually had.

Saddam wanted the CIA and his mortal enemies, the Iranians, to believe he had these weapons.

He believed if they thought he had them, that would be a deterrent.

The CIA did not have the espionage capabilities or the analytical capabilities to put this together, and so informed the world that nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons threats from Iraq posed an existential danger.

The stench of that bad reporting lasted for many years.

- I mean, still, you know, the shadow of it still hovers, obviously, over so much.

You mentioned the Trump era, of course.

We've moved there now.

On his first full day, and we all remember, he did go to the CIA headquarters.

He said, quote, "There's nobody that feels stronger "about the intelligence community and the CIA "than Donald Trump."

That was after he had already cast doubt on the intelligence agency's assessment, as you point out, that Russia tried to meddle with the election.

What did you make of that moment?

How pivotal was that in the integrity of the CIA and where is it leading now in Trump 2.0?

- Well, Trump's speech on his first full day in office of his first term was a desecration.

It was a political speech.

He bragged about his enormous crowds that had turned out for his inauguration, lying through his teeth, as he commonly does, and it was kind of a desecration in the days after CIA officers and analysts put more than a few bouquets in front of the memorial wall where he spoke, in which are engraved the stars of CIA officers who've died in the line of duty.

Something had died, and that was the idea that the president would ever rely on or believe in the CIA again.

Shortly after this, in the wake of the Russian attack on our democracy, a new chief of the clandestine service, top spy, took over his name, which is reported for the first time in the mission, Tomas Rakusan.

His roots are Czech.

He was nine years old when Soviet tanks rolled in to Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring and resistance to Soviet domination.

His feelings about the Russians were intense, bread and the bone, and he called in, this is the spring of 2017, he called in his top operations officers who had spent the past 15 years targeting terrorists.

And by targeting, I don't mean putting warheads on foreheads.

I mean, figuring out who are they, where do they live, what do they think, who do they love, who do they hate, and how can we recruit them to become agents of the CIA?

And he said, "Look here, I want you to take those talents "and train them on the Russians.

"I want you to recruit Russian spies, Russian diplomats, "Russian oligarchs."

And the result of this, four years later, was that the CIA penetrated the Kremlin and stole Vladimir Putin's war plans for Ukraine.

And that marked the return of espionage to its proper place of dominance at CIA.

And stealing that secret, no mean feat, even more audacious, the CIA told the world about it.

Yes.

- And that had a galvanizing effect on the nations of NATO.

At first, they cocked their eyebrows and said, "Oh, really?

"Aren't you the people that told us that Saddam had WMD?"

But when the intelligence proved correct, and the intelligence was not obtained solely by the CIA, it was through liaisons with a large number of foreign intelligence services who work with CIA, including from countries that you would not think of as American allies.

These intelligence liaisons with foreign intelligence services are essential for the CIA to try to be a global intelligence agency.

And they are endangered by the fact that the president has wrecked American alliances all over the world, and by the fact that the president has appointed a collection of crackpots and fools to run the instruments of American national security at the Pentagon, at the FBI, at the Directorate of National Intelligence, and, I'm afraid, at the CIA.

- Well, a lot of people said that John Ratcliffe, who you're talking about, is a pretty decent professional when it comes to this kind of stuff.

He, I guess, they have compared him to other members of the cabinet who you've talked about and come up sort of more thumbs up than thumbs down.

But he did just make a criminal referral of the former CIA Director Brennan, accusing him of lying to Congress and about Trump and Russia.

So again, it's gone back.

You say the reveal of the Kremlin war plan to invade Ukraine marks a high point, a return to a high point in espionage, and now it looks like it's heading down to a low point again of mixing politics and ideology with the figures who are meant to not do that.

So where do you think that's going to lead?

- Nowhere good, I'm afraid.

John Ratcliffe is a political animal.

He has a track record, going back to the first Trump administration, of twisting and distorting intelligence to please Trump.

He has asked the most senior and experienced officers and analysts at CIA to find another line of work.

He has fired everybody the CIA hired in 2023 and '24 at the behest of Trump and Elon Musk.

He has started ideological purity tests for officers seeking promotions, and he has eliminated the CIA's diversity policies.

Diversity is a spy service's superpower.

It's how you don't get caught.

You want people with the cultural background, with the language skills, to blend in to the population.

Terrible decision, all done in the name of political fealty to Donald Trump.

Fealty, blind loyalty to a president, is not part of the job description of the CIA director.

- So much there.

Thank you so much.

Thank you, Tim Weiner, for your book, mission, and for being with us.

- Thank you.

- Now, President Trump's second term has heralded division and uncertainty for many in the medical research community, with cuts to research funding and scrutiny of the health secretary's approach to vaccine policy.

When Dr. Jay Bhattacharya was appointed as director of the National Institute of Health, he pledged to address what he calls the American chronic disease crisis.

And he tells Walter Isaacson how he plans to do so and the challenges ahead.

- Thank you, Krishjan and Jay Bhattacharya.

Welcome to the show.

- Thanks for having me.

- You're a trained physician.

You spent your life studying things like population and chronic diseases.

Why did you wanna take over the National Institutes of Health, which is basically a science medical research institute?

- One of the things that I studied as a, I have a PhD in economics as well as an MD.

One of the things I studied in my former life was science policy.

And I had found a number of things about the way that science worked that made it maybe less productive than it ought to be.

So when I got the opportunity to be the NIH director, maybe we can talk about some of these ideas, but the idea that the science is facing a replicability crisis, that the science that's published often when independent teams look at it don't find the same answer.

Science, although it's incredibly productive, producing incredible results over the past century, decades, millennia, in some ways, the investments we make have not translated over to actually improving population health in ways that maybe it ought to.

So to me, that's the main reason to take it, to make science really work better and translate into improved health for the population at large.

- Back in November, you wrote an opinion piece endorsing RFK Jr. to be Secretary of Health and Human Services.

And you referred to a rot, I think was the word, that had accumulated at the NIH, the place you now lead.

And you wrote, "The National Institutes of Health, "whose annual budget is $45 billion, "orchestrated under the leadership of Francis Collins "and Anthony Fauci, a massive suppression "of scientific debate and research."

What, in your opinion, was suppressed, and is it as bad as you said back then?

- I mean, I think, I mean, I probably would be a little kinder in writing it now than I do, but I do still stand by the idea.

- Okay, let me pause by, why would you be kinder?

- I've had now an opportunity to meet one-on-one with Francis Collins, and we've forgiven each other for whatever has happened.

And he famously wrote, and this is an answer to your first question, he famously wrote an email to Tony Fauci on October 2020, right after I'd written this document called "The Great Barrington Declaration" in October 2020, calling for opening schools, lifting lockdowns, but protecting older people better.

He called me, you know, a Stanford professor, and my colleagues who wrote it, the Harvard professor and an Oxford professor, he called us fringe epidemiologists, and he called for a devastating takedown of the premises of the declaration, which then led to like death threats and all this kind of nasty stuff.

That was an abuse of power.

That was an abuse, it was an attempt to essentially end the debate about the lockdowns from above.

And, you know, I've forgiven him, and I don't wanna dwell on it, but I think that that just, that led then to a whole host of sort of dominoes falling where, you know, you couldn't have a conversation on social media about the lockdowns or about then subsequently about the vaccine mandates and a whole host of other things without getting suppressed.

You could, you essentially, and scientists would call me and tell me that they agreed with me, but they were afraid to speak up because they were afraid that their, you know, metaphorically, their heads would get chopped off.

It made it difficult to have a scientific debate.

- Well, let me unpack what you just said, which is now that you've talked to him and you understand you're both forgiving each other, why did it become so divisive?

And do you think people like Anthony Fauci, Francis Collins made mistakes, or do you think they were intentionally for some ulterior motive trying to mislead people?

- I don't think that, my philosophy about interacting with people is I assume the best is whenever I meet people.

And I don't say that I have some ulterior motive I don't know about, but what I can say, and I entirely agree with the characterization, maybe you don't agree with the characterization, but the characterization that they made mistakes, right?

So, and those mistakes were consequential mistakes, right?

Leading back to even before the pandemic, approving, in my view, a research line aimed at potentially prevent, they were saying to prevent pandemics, but that many people believe may have caused the pandemic, this sort of dangerous gain of function research that people talk about.

- You don't mean the Wuhan lab in China.

- Yeah, I mean, they supported that research, even though many members of the scientific community were saying that that's not kind of wise to do this research.

You know, it's like Enrico Fermi, when he put the nuclear reaction that launched the nuclear age in the squash court at the University of Chicago, he did a calculation asking, what's the probability that this nuclear reaction I've caused is gonna spread around the world unstoppably?

And he found that it was zero.

They supported an agenda, a research agenda, aimed at predicting which pandemics would happen, but carrying the risk of causing a pandemic.

And they said that the risk was worth it.

This is before the pandemic.

During the pandemic, Tony Fauci worked very hard, I think, I mean, in many ways, I think in good faith, I don't know him personally, so it's hard for me to say about his motives, but what he came across as is conveying certainty about things that he should never have had certainty about.

The school closures, the risk of COVID to children, underplaying essentially the evidence of the harms of the lockdown.

And then later with the vaccine, overconfidence about the ability of the vaccine to stop you from getting and spreading COVID.

All of that led to policies that, and we can talk about this in some, but like it led to many, many policies that harmed children, it harmed the working class, it harmed the poor at scale.

And I don't blame just Tony Fauci alone.

He was part of a public health community that embraced this.

But the key thing there to me is that we needed to have a discussion and debate and honest conversation with each other about this.

And that was denied to the American people and the world at large.

There were many scientists that agreed with me that kept their heads down because they didn't want their careers destroyed and damaged.

I would love to see a return to a science where we respect each other's opinions, even though we disagree, may disagree, we may, we'll bring evidence to it, we can discuss whether the evidence is right.

I mean, that's the kind of scientific community I grew up in.

And I'd love to, as the head of the NIH, help the scientific community get back to that.

- Do you think it would be useful to have a commission, a non-partisan expert commission to say, what did we get right?

And what did we get wrong during COVID?

And is it possible in this age to have such a commission appointed?

Who would you put on it?

- Yeah, I mean, I naively, I guess, wrote a Wall Street Journal article in 2021 calling for such a commission.

And then in 2022, I wrote a piece called the Norfolk Group document, where we laid out an agenda for the commission with the hope that other people would add more elements to the agenda.

There've been a number of commissions already.

Like in the UK, they spent a crazy amount of money trying to do a commission.

But the problem is that commissions have been, as your question hints at, really one-sided.

They've allowed the people who led the pandemic response to essentially grade their own homework.

The only way forward with this is to let people, let people who, let a wide variety of views have their say.

Right before I became NIH director, I ran a conference at Stanford where I invited Marty McCary, the current FDA director, as well as some colleagues of mine at Stanford who disagreed with me about the lockdowns.

And it was a really productive conversation.

I think that's the only way forward.

So I guess I'll just continue to be naive about this, but also hopeful.

I think it's possible, Walter.

We just need to come at it with the right spirit.

- Wait, wait, could you just do it?

Could you just announce one?

- I could, but there's a lot of, okay, so let me just tell you the philosophy I've had.

I have a problem that a large part of the country no longer trusts science or public health.

That's a problem for me and for the NIH.

That's just a fact.

Whether you disagree or agree with them or not, that's the fact that I have to face.

At the same time, a large part of the country believes that science was ignored or anti-science forces led to the issues that happened during the pandemic.

And they blame President Trump or Bobby Kennedy or others for this.

My job as the NIH director is to essentially bridge the gap between those two groups.

I believe very fundamentally that science should not be partisan.

There's no such thing as democratic science or Republican science.

Science should be something that is for all the people.

And science can't work for the people if basically everyone distrusts it.

So we have to figure out a way to solve the gap, to solve this divide that we have in this country.

Like we shouldn't be using the NIH as a cudgel to paint Bobby Kennedy or President Trump as anti-science when they're not anti-science.

They care deeply about science.

I've had conversations with the president, I've had conversations with Bobby Kennedy, and they want the scientific knowledge to be translated into better health for people.

You can see it in every conversation I have with them.

And at the same time, I understand why there's this deep distrust.

So a lot happened during the pandemic where regular people look and say, well, why do I have to put a mask on when I walk into a restaurant?

Then I sit down, I can take it off.

How does that prevent the disease?

Why is it that children as young as two in the United States are recommended to get masks, but in Europe, the recommendation was people over 12?

- The NIH, for a long storied history, is supposed to fund scientific research that would be difficult to do in the private sector 'cause it doesn't lead immediately to patents and making money.

And now we've been cutting, it seems to me, some of the NIH funding.

Are you worried about those cuts and do you think we should be basically doing a lot more in fundamental science?

- Right, so Walter, there have not yet been any cuts.

And when I've gone around Congress and talked to folks, what I see, again, from, I've had the privilege of talking to dozens and dozens of folks on both sides of the aisle.

I see basically universal support for the NIH's mission.

And what I see is that, even from President Trump, a commitment to making sure that the US is the leading nation in biomedicine to the 21st century.

I don't believe that the cuts that have been proposed will happen.

I just, as a matter of objectively looking at the pattern of what support there is in Congress and even within the administration.

- I think that you're not totally in favor of those proposed cuts.

You don't wanna deal with Congress and-- - Well, I mean, I'm not supposed to, I'm not to be supposed to, I'm saying this as a matter of, analytically, I'm not saying my personal opinion.

I'm just saying that, and I will say is that the NIH, when it's doing the things it's supposed to do, it has huge benefits for the American people in terms of advanced knowledge that helps cure cancer.

I was just talking actually today, this morning, with some of the folks who were behind the advances that have led to essentially a cure for sickle cell anemia, something that affects a lot of, especially African-American kids, that is seen as, when I was a med student, the idea that you could cure it seemed inconceivable.

- You're talking about genetic editing using CRISPR.

- For instance, yeah, exactly.

And so the cell-based therapies, and now what I was hearing about is you don't even need cell-based therapies.

You can just do it with essentially with an injection.

I mean, it's really, really, really promising.

And that's why you have this bipartisan support for the NIH is because if you can make the NIH focus on its mission, its mission is advancing research that improves the health and longevity of the American people.

Nobody's against that.

Nobody's against that.

And if we actually achieve it, and I believe it's possible we can, it'll secure Americans' health and also biosecurity into the 21st century.

- You know, last month, about 300 staffers in your NIH signed something called the Bethesda Declaration.

I'd love you to be able to respond to it, in which they decried some things happening at the NIH, including politicizing research, they said, interrupting global collaboration, saying, "We're compelled to speak up when our leadership prioritizes political momentum over human safety and faithful stewardship of public resources."

I mean, these are people who work in your building, work for you.

What have you done to address that?

And is there any thing that made you think or change from that?

- Yeah, so just a couple of points about that.

So one, I'm going to meet with them, actually, I think early next week.

I'm going to have them in a round table, and what we can, I mean, I really value this kind of collaborative back and forth, and they're my colleagues.

So I'm going to meet with them or talk with them to see what they're, you know, in person, we can talk through some of the issues.

Just substantively, I think they're just flatly wrong about the international collaboration.

So what I've done as an NIH director, what I learned was that we had a kind of a accounting structure for foreign collaborations where we put universities, domestic universities, in charge of checking whether their collaborators were like meeting basic accounting standards.

And often the people that we put, whether we put in charge of checking this, didn't actually have a lot of control over their foreign collaborators.

Probably most famously, the Wuhan lab, where the NIH funded a domestic group called the EcoHealth Alliance, they had this relationship with the Wuhan lab.

The NIH had no auditing capacity over the Wuhan lab.

There were several, the way we've structured these foreign collaborations prevent, essentially cut the NIH out of the ability to say, well, can you hand us your lab notebooks?

Can we see where you spent the money?

I put in a system that allows foreign collaboration where the foreign collaborators directly connect with the NIH, and so they have the same kind of auditing, we have the same kind of auditing capacity over the foreign collaborators as we do over domestic grantees.

That's going to allow more firm, more foreign collaboration and more effective collaboration in a way that I can look the American people in the eye and say, we're spending your money in a safe, we're stewarding your money in the right way.

We're checking to make sure that those collaborations are productive and we can audit them in the ways that we audit domestic researchers.

So I'm going to, I'll tell them about that 'cause I think they just didn't understand some of the changes.

As far as politicization, I've worked hard, I think I can probably tell the story in terms of the USAID where it was really cleanest.

The USAID had these programs like PEPFAR.

PEPFAR was this program to bring HIV medications to Africa.

I'd written a paper in 2010 or 11, estimating that PEPFAR had saved over a million lives by at that point in Africa.

I think it's a great program.

The USAID also had this program to add a third gender to the Bangladeshi census.

Now, Walter, Bangladesh has a tremendous problems.

It has arsenic in the drinking water.

It has hundreds of thousands of children dying of viral illnesses.

It has all kinds of issues.

Adding a third gender to the Bangladesh census looks to me like a politicization of the USAID rather than something that's really within the USAID's mission.

There were elements of the NIH portfolio that were also like that, essentially trying to use the NIH as a weapon in a political war that we're really poorly equipped to fight.

The DEI, for instance, I think that's something that the NIH, I really strongly believe in we should invest in minority health.

If minority populations have worse health outcomes and have bad health outcomes, we, the NIH, as part of our mission should invest in improving the health of minority populations.

A hundred percent believe in that.

But what did those DEI investments actually do?

Did they actually improve minority health?

No, minority health is lagged behind just as it has the health of many, many other American groups.

We have to use the NIH to improve health rather than use the NIH in the part of an ideological political war.

So I think removing that, which they're calling political, is actually depoliticizing the NIH.

It leaves the NIH portfolio in a place where every party can look at this and say, we are doing the right thing for the American people.

We're advancing, we're investing in science that will improve your health, improve your outcomes.

We're not trying to fight a political war that we're poorly equipped to fight.

We just shouldn't ever be fighting.

We should be scrupulously apolitical in that.

And that's really the transition to that, I think, has made a lot of people uncomfortable because that's really what it was before.

We had this, if you will, this third-gender Drobanginesi census problem, although that's the USID.

We had a version of that in the NIH.

- Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, thank you so much for joining us.

Appreciate it.

- Thank you, Walter.

- And that's it for our program tonight.

If you want to find out what's coming up every night, sign up for our newsletter at pbs.org/amanpour.

Thank you for watching and goodbye from London.

(upbeat music) - [Announcer] "Amanpour & Company" is made possible by the Anderson Family Endowment, Jim Atwood and Leslie Williams, Candace King Weir, the Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poita Programming Endowment to Fight Antisemitism, the Family Foundation of Layla and Mickey Strauss, Mark J. Bleschner, the Philemon M. D'Agostino Foundation, Seton J. Melvin, the Peter G. Peterson and Joan Gantz Cooney Fund, Charles Rosenblum, Ku and Patricia Ewan, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities, Barbara Hope Zuckerberg, Jeffrey Katz and Beth Rogers, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

(upbeat music) - You're watching PBS.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

New NIH Director Dr. Jay Bhattacharya: “Science Should Not Be Partisan”

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 7/18/2025 | 18m 24s | NIH Director Dr. Jay Bhattacharya discusses the challenges facing the agency. (18m 24s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: